The economic return was spiced up by the controversy initiated by the book, to say the least committed by Cahuc and Zylberberg, two economists claiming to be orthodox, on what they call "economic negationism". This negationism would be the tendency of certain intellectuals to ignore the results of economic studies or even to reject the economy altogether, as an ideology at the service of the dominant class.

Heckling in the halls of the university

The economists targeted are notably those who present themselves under the label of heterodox. The response from some of them was not long in coming. In particular, they describe Cahuc and Zylberberg's book as "a pamphlet as violent in tone as it is mediocre in content". According to them, “never has the attack been of such a low level”.

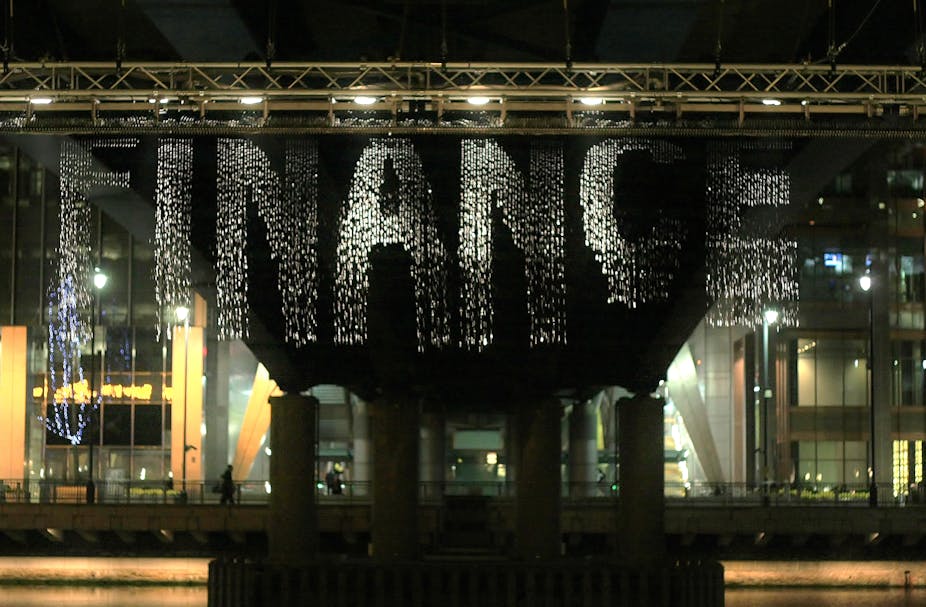

Beyond the intellectual tussle that is unfolding before our eyes, the book raises the interesting question of the character of “science” of our economic disciplines in the broad sense. Moreover, this question arises for economics as well as for management sciences. As such, finance is at the conjunction of several disciplines (economics, management science, applied mathematics, etc.). We are therefore going to try to answer this question of scientificity for a branch of the economy: finance.

Classical finance, a science?

Let us first recall what can be understood by “science”. A science consists, through a precise methodology, in understanding and explaining the world. We start from observations that bring out a falsifiable theory and therefore hypotheses that we test and which make it possible to invalidate or support the theory in question. Until then, finance meets the definition. However, a science also aims to derive accurate predictions from this knowledge. And this is where the shoe pinches.

Because even in the case of finance, an economic field in the broad sense where data and observations are very abundant, the predictive power of models remains relatively weak. For example, the greatest achievement in financial economics is probably the CAPM, the famous Financial Asset Pricing Model. Without going into details, it allows once we know the movement of the whole market to know the expected profitability on a title in particular. It correctly predicts about 60% of the variability in stock movement. To give the reader an idea, models in physics are generally not considered valid below 90%. Economic systems are indeed complex, depending on the aggregation of the decisions of many economic agents, which makes economic prediction difficult.

In addition, finance traditionally uses mathematical demonstrations to create its models. This state of affairs does not fail to annoy certain financiers in that they would like to put the human or even the political at the center of the debate. Mathematical demonstrations are necessarily based on axioms and hypotheses. One of the main hypotheses is that of the rationality of agents. However, it has been clear since 1953 and the French Nobel Prize winner Maurice Allais, that this hypothesis does not hold at the individual level. For the anecdote, Maurice Allais notably proposed a questionnaire during an economics conference in Paris, to test certain basic axioms of rationality. Luckily, one of the popes of orthodoxy in economics, Leonard Savage took part in it.. His choices violated the axiom of substitution. He later admitted his error, and attributed it to the presentation of the choices that were offered in the questionnaire.

Behavioral finance to the rescue

This led to the creation of a field of behavioral finance: we can read on this subject the writings of Robert Shiller , who, paradoxically, obtained the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2013, at the same time as Lars Peter Hansen and Eugène Fama (considered one of the founders of the theory of efficient markets).

Behavioral finance comes from the application of psychology to economics. It is a matter of relying on psychology to shed light on and better understand economic phenomena. This field is particularly interested in many deviations from rationality in financial markets. These biases go against the famous theory of efficient markets.

The full list of such deviations is long. An example is the Monday effect : the tendency for markets to be more up on Friday and more down on Monday, which could be attributed to a mood effect of market operators. And yes, nobody likes Monday! Weather effects are another example. Instead, the market tends to go up on sunny days and down on bad days, again due to a mood effect.

However, most of these biases tend to disappear once highlighted, an argument rather in favor of market efficiency. Moreover, behavioral finance is often criticized too, because it lacks a global theoretical framework and does not really improve the predictive power of classical models. It is more like a collection of observed phenomena, most of which can be explained by the emotions of economic agents.

0 Commentaires